My Continuing Journey with the Feldenkrais Method

August 2023

As blog number 1 on the new website, I thought it would be fun to share my experience with the Feldenkrais Method in my cello life, both as a player and teacher. I’m becoming increasing committed to the work as a wonderful resource for cellists, all musicians, and anyone really! I was honored last week to have the opportunity to present a session for CelloBello’s “Teacher Training Seminar” titled Applying Feldenkrais Principles in Cello Teaching. What I write here is largely based on that presentation.

For those not familiar with Dr. Moshé Feldenkrais’ way of freeing and developing the human experience, it can be summed up with the following description: “The Feldenkrais Method is an educational system that uses movement to teach self-awareness and improve function.” For more general information, I refer you to this website.

I’ll start with some quotes to keep mind while reading through the blog.

–Pablo Casals: “The most important thing an artist needs to be able to do is forget everything they’ve learned.”

-Mstislav Rostropovich: “The bigger you play, the more relaxed you need to be. When I play softly for a long time, I need to play loud again to rest.”

-Janos Starker (as told to Paul Katz). “I can best describe my entire lifetime of cello playing as the continual discovery and release of smaller and smaller points of muscular tension.”

-Yehudi Menuhin: “More and more we realize that practicing is not forced labor; more and more we realize that it is a refined art that partakes of intuition, of inspiration, patience, elegance, clarity, balance, and, above all, the search for ever greater joy in movement and expression.”

Pablo Casals: “Just play naturally.” (title of a wonderful book by Vivien Mackie on Casals’ teaching.)

So, the story. Throughout my 20s I searched for a way to feel less awkward at the cello and play with comfort and physical pleasure rather than struggle. I rightly believed that this was an essential part of fulfilling my musical and cellistic potential and goals. The search first brought me into contact with the Alexander Technique, which I studied for about four years. This was definitely moving me in the right direction, but not as far as I wanted to go. I tried some yoga, some Dalcroze Eurythmics, some body mapping, reading some books like The Inner Game of Tennis, and I finally took some Feldenkrais lessons in my late 20s. (My last teacher, Raya Garbousova, gave me The Inner Game of Tennis and told me “this the best book on cello playing that I’ve ever read!”) Feldenkrais’ approach seemed to bring it all together and provide the very best support for my search. At that point my life also turned in various other musical directions, and performing on the cello was put to the side. But I continued to teach the cello, mainly to gifted teenagers, many of whom were very ambitious and often sought to study at a high-level Conservatory, so the search continued largely for their benefit. I’m happy to say that this was constant thread in life and often kept me sane and grounded amid the challenges and stresses of conducting, administration and many, “social action through music” El Sistemas initiatives. I don’t have to tell cello teachers what joy we feel in the act of nurturing the lives of young people through our noble art and our beautiful instrument!

One of the themes that runs through nearly all discussions of how to achieve better cello playing is combating tension, our number one enemy. There are endless strategies for this, and it’s been on my mind as a teacher constantly from the beginning. I tried many approaches with varying degrees of success, even becoming known as a teacher who is pretty good at “loosening kids up.” I had stopped studying Feldenkrais, but one day a student came to me who had become blind as an infant and was expected to be mentally and physically handicapped for the rest of his life. Eventually, his sight became better and his mental faculties improved. When he started lessons with me at age 14, he had developed a burning passion to play the cello! His work on the on the instrument clearly had had a beneficial effect in the overcoming of his disorder, but he was constantly frustrated, because coordination was a huge challenge, and his body just didn’t respond in the way that allowed him to fulfill his lofty musical goals. I recommended some Alexander lessons, which helped, but then I thought, why not try Feldenkrais. I introduced him to my colleague Uri Vardi at U Wisconsin who is an excellent cellist and teacher, and an outstanding Feldenkrais practitioner/zealot. You might know of his many summer workshops, often titled, “Your Body is Your Stad.” http://www.harmoniousmovement.com My student wound up doing undergraduate work with Uri Vardi and then completing master’s degrees at CIM and the Amsterdam Conservatory. Clearly, he had overcome completely that serious disorder, and we both agree that Feldenkrais work was an essential element. Once in Amsterdam he became even more fascinated with the method, became a practitioner himself, and became the Feldenkrais teacher at the Amsterdam Conservatorium.

The student’s name is Michael Tweed-Kent, and a couple years ago I reconnected with him and learned that he was doing groundbreaking work making Feldenkrais practices helpful to musical performers. He works with all the instruments and voice at the Conservatory but, , as a cellist, he has an innate understanding of the challenges we face. Over the last three years several of my students and I took three online courses with Michael, first on the bow, second on the left hand, and third on the relationship between the two. The first was eight hours and the second two were six hours. There’s a lot to say and learn on the subject!

I recommend that you seek Michael out if you’re a musician and you’d like to know and experience more about the Feldenkrais approach In fact, most of what I’m sharing here comes from Michael’s workshops and private lessons. https://www.feelgoodsoundgood.com

Studying Feldenkrais brought me into a beautiful new relationship with the cello. I began to really enjoy the experience of playing, to anticipate with excitement my 3 to 4 hours of practicing each morning, and to feel deprived when something prohibited me from doing it. Believe me, this is the first time in my life experiencing that! It led to even more joy and effectiveness in teaching. It even gave me the courage start performing again. I gave four presentations of a recital program this spring, the first recital in about 35 years. And it was a real pleasure!

Since starting Feldenkrais work, I’ve been intrigued by the challenge of figuring out how to bring Feldenkrais principles into the studio in a practical, understandable and efficient way. Having worked at this intensely for several years, experimenting on myself and my students, I’ve become convinced that this is a fantastic resource for all music teachers and players. I feel I’m just getting started on this journey of understanding, but I’ll share here some discoveries and some developing ideas.

I’ll start by identifying some of the Feldenkrais principles as outlined by Karen Clay, a wonderful Feldenkrais teacher. Each one is followed by some of my own comments. I believe that musicians will feel resonance with many or most of them in their own playing and teaching!

Proportional Distribution of Muscular Effort

The big muscles do the big work

and the small muscles do the small work.

MC: This is what instrument musicians are always striving to do so our hands and arms can feel supple, sensitive, and responsive, but strong at the same time.. Feldenkrais said that it should be as easy and gentle to lift your leg, arm, or head as it is to lift a finger. But only when the big muscles are fully employed.

Balance/Counter Balance

Improved balance is achieved when the center of body mass is clearly organized over the base of support.

MC: being balanced is extremely advantageous to movement of any kind and, of course, to cello playing! I’ve always tried to teach students to find the center of gravity in themselves and to let it be as low as possible as the physical foundation of good playing. They work on this while standing, sitting (without and with the cello), bowing, shifting, etc. Those who practice and teach martial arts are always focused on this. Paul Katz, in his introduction to Victor Sazer’s New Directions in Cello Playing, states: “It is far better for cellists to learn from the martial arts which focus on balancing the body, loosening joints, relaxing muscles, using body weight rather than flexed muscles for strength and breathing in ways that promote balance and ease. Motion functions naturally when unimpaired and brings agility, vibrancy and power (explosive if needed) to any activity.”

Breath Is Free in Activity

Held or restricted breath is a manifestation of strain and effort,

while ideal movement is coordinated

with uninterrupted and easy breathing

MC: A very big subject for cellists and all musicians! I’ve spent most of the life holding my breath or breathing unnaturally when trying to accomplish any demanding task. I was always aware of this when I played, especially from the noises that were coming out of my mouth… But how to effectively deal with it eluded me. I’ve found that the most effective way to promote free breathing is to develop the awareness and sensitivities that Dr.. Feldenkrais aims at.

The carriage of the head serves to tonify the entire body

MC: The Alexander Techique is centered on this idea. The method promotes the idea of “Primary Control” or that the proper relationship of the head, neck and back allows for an integrated body and all the benefits that we aspire to in this blog.

Mature Behavior

Is the ability to act spontaneously.

A mature human responds to the environment and its unexpected situations without compulsion.

The response is effortless, making effective use of self, and allows the possibility of failure.

MC: There are so many surprises that occur when we’re playing: missed notes, awkward shifts, undesirable sound, etc. How we react physically and emotionally to these situations can be freeing or constricting, depending on having this ability or not. We have a reaction to making mistakes in our youth orchestra: we throw up our arms and say “how fascinating!” with a smile. Trying that is a great place to start!

Evenly Distributed Muscular Tone

No Place works harder than any other place.

A well-organized person experiences lightness and ease of movement.

MC: This principle is related to balance of course. I can say that Feldenkrais work really promotes this ability to organize ourselves in this way. Another great asset to good playing!

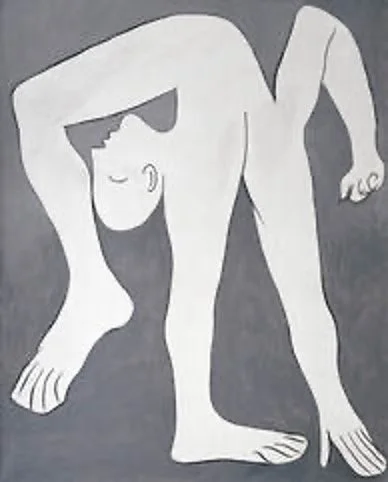

What Is Good Posture?

The state from which a person is able to move in any direction,

at any time, without hesitation or preparation.

It is the absence of unnecessary muscular contraction.

As a starting point for our movements and actions, posture

(or more exactly, “acture,”) dictates our movement potential.

MC: Dr. Feldenkrais said ““Good posture is the ability to move in any direction without preparation.” We need to get past the idea that holding ourselves in a certain way is good posture. If you’re slumping in a chair, you can have good or bad posture. You can try going on all fours and imagine moving any part of yourself in any direction. You’ll likely find that your body begins to organize itself in a way to allow you to do that if you stay out of its way! You’ll feel muscles loosening and body parts realigning. You can imagine the advantages to this kind of “good posture” in playing

Learning By Doing

Experiential learning is the process of making meaning from direct experience.

Knowledge may be continuously gained through

personal, exploratory interaction with the environment

MC: I think the key word here is exploratory. Trial and error. But have in mind what we’re working to achieve: ease, freedom, balance, etc. that leads to more effective and joyous playing!

The Nonlinear Nature of Change

Differences in action or environment may trigger nonlinear changes.

By varying the environment of familiar task demands, it is possible to destabilize postural habits and help new ones to emerge.

MC: We should try to constantly vary our environment. In cello playing, for example, this can be the way we sit, bow, shift. It’s best to try different ways constantly. Don’t get stuck. Yo-Yo Ma is a huge example for us in this area, as well as all the others of course! We’ve all seen him grab his cello and play standing up, with a cello on the side, slouching, in any position. And of course, he moves constantly, changing his playing environment. We see that he is able to instantly respond to any different environment in ways that doesn’t reduce the effectiveness of his playing in any way. You can see this in all his videos, especially of his teaching. Also, when Rostropovich was asked, “How are you able to play Elfantanz so fast and effortlessly?” he responded., “by constantly changes the muscle groups that I’m using.”

Orientation

is a biological necessity and essential to all action.

Spatial relationships and coordination are determined by orientation.

MC: This one is a little abstract for me, but I find it’s very useful to sense your relationship to the floor, walls, ceiling of the room that you’re playing in. This can really help with balance and evenly distributed muscle tone.

Reversibility

The sequential character of a movement that enables one to stop or change direction at any moment without holding, falling, or experiencing a moment disturbance.

MC: Isn’t this what we spend our lives figuring out how to do as musicians? On the cello, bow changes, string crossings, changes in the direction of shifts, moving back and forth between fingers all require the highest degree of reversibility.

The Weber Fechner Law

When effort is decreased, one can discriminate finer sensory changes, leading to greater potential for learning.

MC: Maybe the number 1 principle in practicing and teaching! The difference between training and educating ourselves.

To Correct is Incorrect

When working with self and others,

force is not directed to create a specific outcome;

rather one elicits the person’s ability to self-organize.

MC: This is also elusive, because we’re all so goal oriented. Alexander has a lot to say about this subject, what he called, “end-gaining.” In teaching others or ourselves it’s often best to work with what’s there, or what we or our students are already doing. e.g. if a student has a high shoulder, suggest holding the shoulder even higher to experience more discomfort. Then suggest that they find ways to reduce the discomfort and make playing easier by letting the body self-organize. Often this leads to more improvement than just saying something like “be sure to keep your shoulder relaxed.” This is also called “old way/new way” or wrong way/right way learning.” I find it’s one of the very most effective ways to change physical habits for the better on the cello and in life.”

We Act in Accordance with Our Self Image

This self-image ~ which in turn governs our every act ~

is conditioned by three factors:

heritage, education and self-education.

MC: Becoming aware of our self-image and learning that we can change it opens new worlds of possibility to us. I refer you to a chapter in the book by my dear friends Ben and Roz Zander: The Art of Possibility. The chapter is called “It’s All Invented.” In other words, all the stories that we tell ourselves about who we are, what are our limitations, what we can and can’t accomplish, etc. are inventions, and we can just change those stories about ourselves, and without much effort, especially when we become aware of how those three factors have created those stories in the first place.

Here are a few other common Feldenkrais principals to contemplate.

-Force travels longitudinally through the bones

-Head and eyes are free in any activity, no matter how difficult.

-Slowness of movement is the key to awareness, and awareness is the key to learning

-Differentiation – making the smallest possible sensory distinctions between movements – builds brain maps

And a top-of-the-head list of Feldenkrais principles from Michael Tweed-Kent:

-bones instead of muscles

-learning instead of training

-function instead of posture (for cello playing thed function is string and sound)

-vary contantly

-reducing effort

-cleaning the beginnings of movements

-power from the pelvis so arms and hands can be soft

-freedom of the head

-ease and independence of breathing

You can find a very informative interview with a Feldenkrais teacher on the Suzuki website. https://dev.suzukiassociation.org/news/feldenkrais-method/ Highly recommended!

Lastly, some advice to all teachers for us to heed from Feldenkrais practitioner, Alex Toennige. Again, wonderful advice for playing, practice, teaching, and living!

Do Only What’s Easy: Having the learner do only what’s easy will allow him or her to understand with more clarity and discernment.

Go Slowly: Going slowly will allow the brain to better absorb and integrate new information. Slowness is the key to awareness, and awareness is the key to learning. Speed will increase on its own with time.

Start Small: You’re more interested in how learners do the process than how much they do. Starting small will allow for the most improvement, as differentiation is easiest when the stimulus is small. Have them start off small, and they’ll soon surpass your expectations.

Look for the Pleasant Sensation: If it feels good, they’ll want to do it again! The brain is always looking for the easiest, most efficient way to do anything.

Let Learners Make Mistakes: Errors are essential for learning. Think about how a baby learns to crawl, walk, or speak. Random, spontaneous ideas lead to developmental breakthroughs.

Pause Often: Allow the brain a moment to take in new information. Beginning again with fresh attention will pique curiosity and allow for better learning. Let interest dictate the pace of learning.

Reduce Unnecessary Effort: When learners use less effort, the improvement happens automatically rather than through force, and the process becomes more fluid and facile.

Don’t Try: When learners are goal-oriented, they’re likely to use extra effort and get in their own way. The human brain learns best driven by curiosity rather than pressure.

Use the Imagination: The learner’s brain fires in the same way when visualizing something as when he or she is actually doing it and can sometimes even allow the learning to happen faster. Use this creatively!

Be Gentle: It’s not helpful to ‘correct’ learners or create competition or deadlines. Allow them to be present, curious, and engaged with the process, and the improvement will happen on its own.

If you’re a musician and you’re intrigued by all of this, just Google “Feldenkrais for musicians.” You’ll find that more and more musicians are becoming Feldenkrais teachers because of the effect that the method had on themselves, many music schools and departments have a Feldenkrais teacher on staff, and there’s a strongly growing curiosity about the method as we strive to play and teach more wholistically, with both ease and strength!

Lasty here you can find a plethora of quotes from Moshé Feldenkrais. Many will really hit home!

To be continued!!